Heinz-Günter G. Floss

August 28, 1934 - December 19, 2022

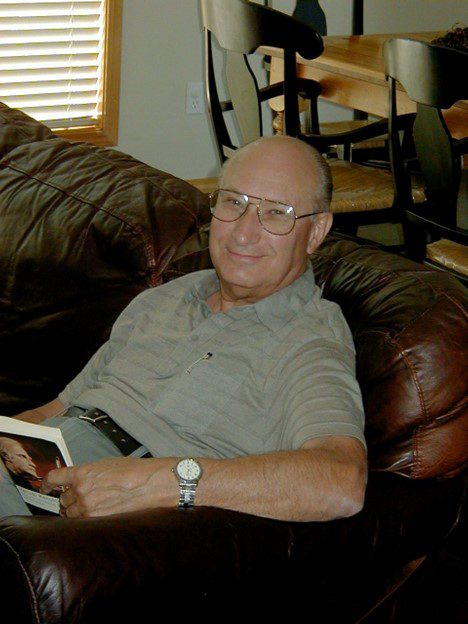

Heinz-Günter Gottfried Floss was a renowned scientist, a beloved father and grandfather, and an utterly devoted husband. He was born on August 28, 1934 in Berlin, Germany, the only child of Friedrich and Annemarie Floss. Doted on by both his parents and extended family, his early years were happy and, in his own words, “uneventful.” This changed with the onset of World War II when he was five years old. Growing up in war-torn Germany was arduous, specifically with Berlin being a target of significant bombing, which led to him and his mother evacuating the city. Heinz-Günter’s immediate postwar years in Berlin were hungry and difficult, but as Berlin returned to stability, so did his personal life.

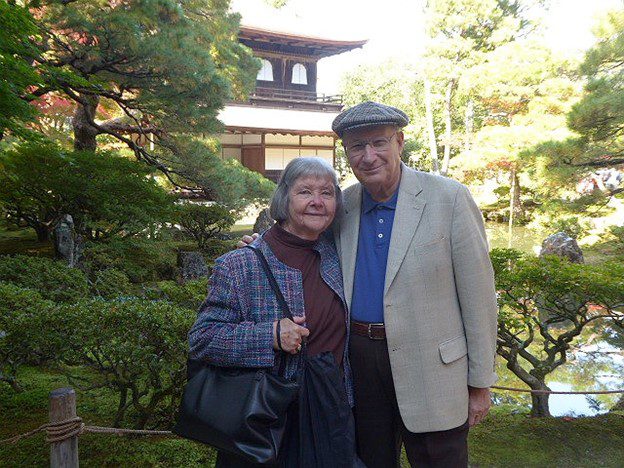

Just before completing high school and beginning his university studies, his life changed dramatically when, on a double-date bicycle ride with a school friend, he met a young woman named Inge Clara Luise Säuberlich. A spark lit between the two of them at once and in Heinz-Günter’s own words, “the bike trips for four soon turned into bike trips for two. I don’t remember all the places we went to around town, because it didn’t really matter where we went, as long as it was the two of us.” This sentiment would eventually take Heinz-Günter and Inge from all over town to all over the world, including immigrating in 1966 to the United States with their family, settling first in West Lafayette, Indiana and eventually making their home in Bellevue, Washington. Wherever he went, they went, and they went very happily together.

If anything characterized Heinz-Günter as a person, it was his total devotion to his wife, Inge. During a period of parentally-enforced separation during their courtship, he often hung around her family’s apartment in the evenings, “like a love-sick tom-cat, hoping to catch a glimpse of her,” and in later years, Inge nicknamed him “Hundi” for his puppy-like attachment to her. In defiance of Heinz-Günter’s father, they married in 1956. In spite of the initial tension this caused with his parents, marrying Inge proved, in a lifetime of excellent decision-making, to be the best and happiest decision of Heinz-Günter’s life. Thereafter, he was rarely separated from Inge, taking her with him on work trips and everywhere else he could. Heinz-Günter was a man who knew how to hold onto a good thing when he found it.

Four children, Christine, Peter, Helmut, and Hanna, followed this union, to whom he was a loving and committed father. He nurtured in them an appreciation for culture and the world around them, taking them on trips that ranged from hiking vacations in the Swiss Alps to detailed tours of the California Spanish Missions. He also fostered an understanding of the sciences, performing experiments for them with dry ice or dipping roses into liquid nitrogen, and putting them to work washing beakers in his lab.

He likewise enjoyed spending time with his grandchildren, and imparted unconventional wisdom such as “there’s no barometer for taste” and recommending that you like the way your partner smells, as well as more traditional counsel on career decisions, travel plans, and how to make the most of one’s life. He regularly orchestrated family reunions, and on one such occasion in 2016, he spoke emotionally on how much it meant to him to have such a large and loving family come from the small beginnings of two only children.

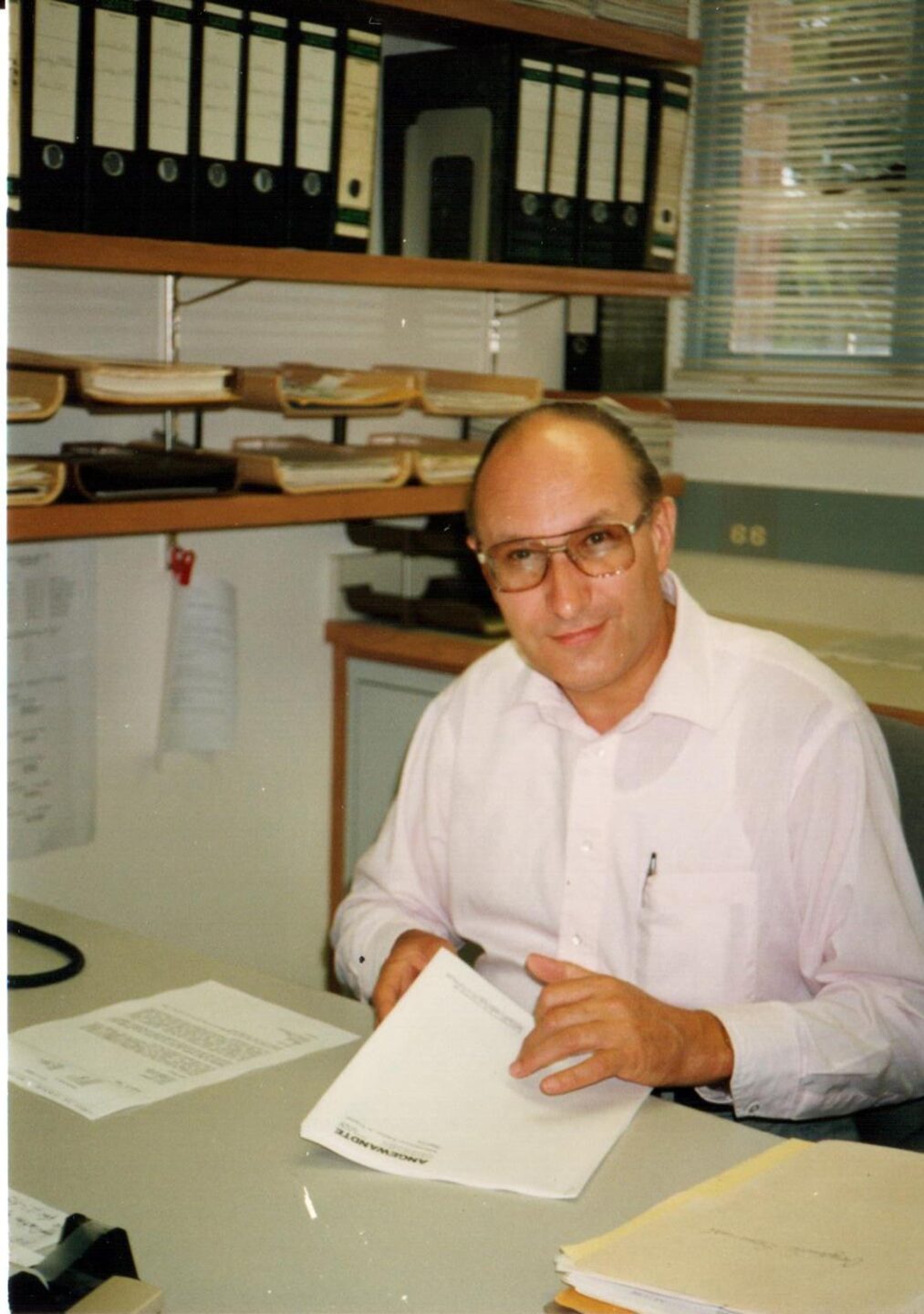

Heinz-Günter received his Ph.D. in 1961 studying organic chemistry at the Technical University of Munich, where he worked with Friedrich Weygand in Munich and Kurt Mothes in Halle. To work with Mothes, who was based in East Germany, Heinz-Günter had to overcome complex political barriers during the rise of the Iron Curtain. Heinz-Günter, Inge, and their young children spent a short time at the University of California, Davis for his postdoctoral work before settling in Indiana as a professor of Medicinal Chemistry at Purdue University. In 1982, he moved to The Ohio State University, and to the University of Washington in 1987.

Throughout his career, he worked on biosynthesis (harnessing biological processes occurring in microorganisms to create complex products) of antibiotics, anticancer drugs, and ergot alkaloids (used to treat migraines), including genetic engineering of hybrid antibiotics. His work, along with that of his collaborators and students, developed a wide array of biosynthesized products used for a variety of medicinal purposes, and led to a “renaissance” of such natural products over non-biologically synthesized, less complex medicinal products. Over his time as a professor, Heinz-Günter advised 70 Ph.D. students and mentored more than 75 postdocs. To quote an early postdoc he mentored, John Vederas, “the legacy of a professor is in the education and long-term inspiration of new researchers, who then transmit this in their own way to the next generation. In this regard especially, Heinz[-Günter] has been a true grandmaster who has educated a host of accomplished scientists and profoundly influenced the way a very large field of science has developed.”

Outside his scientific career, Heinz-Günter remained relentlessly curious. He was an avid admirer and collector of the arts, and particularly enjoyed electronic musician and Buddhist priest Kouei Nishimura, Japanese potter Shoji Hamada, and indigenous art of the American Southwest and Pacific Northwest. He traveled widely and as often as he could, frequently returning to Germany, Switzerland, and other locations across the globe. Just weeks before his death, he was finally able, post-pandemic, to return to Kyoto, Japan, one of his very favorite places. He enjoyed hiking, swimming, and frequent visits to the Bellevue Botanical Garden. He was known for his jovial sense of humor, thorough travel itineraries, cheerful willingness to purchase all the books his wife wanted (not a small number), and his enthusiastic ability to scrape a jar of Nutella perfectly clean. A prolific writer, he leaves behind a treasure-trove of thoughts, memories, and jokes in his travelogs, family emails, and personal memoir.

He is survived by his beloved wife, Inge, with whom he enjoyed sixty-six years of wedded happiness; his sons Peter (Barbara) Floss and Helmut Floss; his daughter Hanna (Tony Andrews) Floss; grandchildren Alisha (Jeff) Hillam, Ashley (Jeremy) Jewell, Brian (Kristiana) Floss, Michael (Tia) Floss, Maggie Yuse, Amanda (Daniel Musselwhite) Stadermann, Ben Yuse, Elizabeth Andrews, and Tyler (Emily) Andrews; and great-grandchildren Minnie Hillam, Ezra Hillam, Ruby Hillam, and Elise Andrews. He is preceded in death by his parents, Friedrich Heinrich Floss and Annemarie Floss née Günther, his daughter Christine Floss, and son-in-law Frank Johannes Stadermann.

In lieu of flowers, the family suggests a donation in Heinz-Günter’s memory to the Bellevue Botanical Gardens where he and Inge walked regularly.